The folk art of pre-industrial Japan—the bowls and boxes and kettles and pickle jars made for every-day use by unknown craftsmen—is amazing stuff. In mingei (“the people’s art”) you can catch a glimpse of the same inspired simplicity that characterizes the furniture of the American Shakers. There is a genius to it.

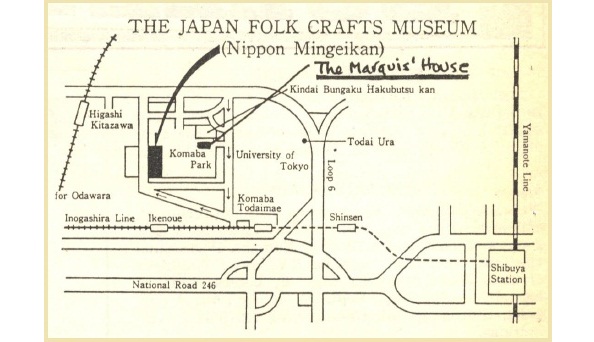

A visit to the Mingei-kan, the wonderful museum devoted entirely to Japanese folkcrafts which some people think is the city’s best museum of any kind, perhaps followed by a short visit to the elegant Japanese house and garden of the late Marquis Maeda just down the road, makes a pleasant half-day excursion.

Take a local Inokashira Line train from Shibuya Station to Komaba Todai Mae, two stops down the line, fare ¥90. (You might find it fun to ride at the front of the train where you can watch the motorman go through his highly disciplined drill, pointing a white glove to each signal as it comes into view, as though cueing in the brass section.)

Seven minutes later, two stops away from Shibuya and you are out in the country. Trees! Birds! Oxygen!

Take the Todai exit from the station (to the left at the top of the stairs) and as you leave the station you will see in front of you the gate and clock tower to Tokyo University, the pre-eminent institution of learning in this learning-drunk country. You can take a stroll through the campus if you like, but be forewarned that you will find here no ivy-covered collegiate gothic or even any architecture of much interest at all. In truth, the campus is a slum. Very strange, considering what it might be.

Follow the road which goes down to the left as you leave the station. The train tracks will be off to your left. Stay on this road (it winds a bit through one of Tokyo’s best-heeled suburbs) until it swings around to the right, past the private tennis courts of the Sumitomo Fire Insurance Company. The museum is on the right-hand side of the road, unmissable. It’s a ten-minute walk at most.

Slip into one of the dozens of pairs of the Mingei-kan’s slippers lined up just so at the entrance and pay a ¥700 entrance fee at the little administrative office.

The museum was built 50 years ago to accommodate the extensive folk-art collection of Soetsu Yanagi, a professor at the University of Kyoto who travelled the country buying and cataloging the objects of everyday living which were just on the edge of being lot or thrown away. In this way, Yanagi single-handedly founded the folkcraft movement in Japan to preserve this country’s craft heritage, and not a moment too soon.

Now the Japanese come to Mingei-kan, the shrine of the movement, to marvel at the sensibilities of their forefathers, much as Americans take pilgrimages to Williamsburg, Virginia. “How clever they were in the old days, and how much we have lost by our own accursed cleverness,” said one lady on seeing a display of dazzling summer kimono worn 200 years ago by farm workers in Okinawa. It was a typical comment.

The building is small and designed with considerable flair, an adaptation of the design of a 150-year-old residence in Northern Japan, but with modern lighting and fixtures. The great sweeping staircase with wide oak banisters has an old clock on its landing which chimes the hours. The showcases holding the artifacts are like pieces of furniture and there are comfortable old chairs and benches to sit on while you contemplate the wonders all around you.

What must have been the quality of the life of these people if this is the beautiful little bottle they poured their sake from each evening, probably without even thinking about it?

On the second floor of the 50-foot-long gallery, one of Tokyo’s finest exhibit spaces, whose walls are hung with kimono, scrolls, straw work and kites. In the corner is a fierce-looking strong box with a brass lock and family seal, colored the most delicate shade of shu. Outside in the roof garden, set against a grove of bamboo, is a collection of the huge pots where a family would store their salt, soy sauce, sake and water.

You will notice how subdued the colors are, now quiet. These are objects for the use of ordinary people, not high officials, so it wouldn’t do to be flamboyant. But the care put into the details of even the most matter-of-fact object, even a straw rain cape which would last a month or a little container to store pieces of charcoal which have been only half consumed so they can be used again later. Of course, the rural people who made those things must have had time on their hands during the winter months when it was not possible to work in the fields.

Time: what a luxury.

Look at the shape of this 250-year-old lacquer bowl — as graceful as a signed piece of modern Scandinavian art.

Take as long as you like. The museum will not be crowded. Some people spend hours sketching here, and it is quiet.

Before you leave, take a look at the museum shop. You might well find something you would like to take away with you to remind you of this place. Lacquer bowls are ¥1,000 to ¥5,000, hand woven traditional textiles are ¥2,000 to ¥10,000 a meter, and there are some splendid furoshiki for ¥3,300.

[Lunch? Back down the street toward the station you will find “Miyagawa,” a tiny little shop where you can have unaju, eel broiled over charcoal on a bed of rice for ¥1,200, made the old way. “Miyagawa” has two tables and a little tatami area, doing most of its business by demai, that is, taking orders from the neighborhood over the phone and delivering by bicycle. Closed Thursdays.]

After lunch you might want to wander to Komaba Park to visit the Japanese house of Marquis Maeda—I say Japanese house because the good marquis, who served as naval attache in London, also had a magnificent Western-style house just next door, and this is also open for inspection on payment of a small fee.

But the Japanese house is the thing. Just wander in; there’s no admission charge. The main room is 50 tatami mats, which in Japanese terms is huge, and it is absolutely devoid of decoration of any kind. It looks out on a wonderful panoramic garden of rocks and carp pools and carefully groomed pines. Sit out on the little veranda and listen to the caws of the crows.

The address of Nippon Mingei-kan is 4-3-33 Komaba, Me-guro-ku. Tel. 467-4527. Open 10-5, except Mondays.

If you would like to explore further modern Japanese crafts, you might want to visit Takumi, 8-4-2 Ginza (near Hotel Nikko), tel: 571-2017, or Bingoya, 10-6 Wakamatsu-cho, Shinjuku, tel: 202-8778.