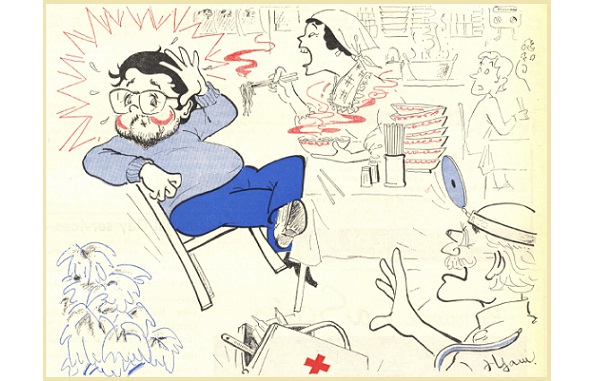

Our resident eater Mark Schreiber uses the ol’ noodle in run-down on local fave fare

It was the winter of 1967-68, and a cold, snowy winter it was in Tokyo that year. The kerosene space-heater in the old geshuku (boarding house) in Chofu city fought a losing battle to keep the six-and-a-half-mat tatami room temperature above the freezing point. Atop the heater teetered a battered aluminum saucepan; in it, a packet of Sapporo Ichiban instant noodles foamed and bubbled their way to al dente consistency.

The 20-year-old American paused from the kanji lesson in his “Japanese for University Students” textbook to plunk in a raw egg and give the broth one final stir before transferring the contents to a large plastic bowl. Cupping the bowl in both hands — to warm them — before taking up disposable chopsticks, he raised it to his mouth. The hot broth fogged his glasses, rendering him momentarily sightless in a cloud of shoyu-scented steam…

That student was me, and the impoverished circumstances of my first years in Japan were such that for a long time afterwards I lost the desire to consume ever again ” another bowl of “instanto ramen.” “Noodles, nevermore,” raved the raven.

But whether it appeals to your discriminating taste or not, it cannot be denied that instant ramen has become, after rice, a Japanese dietary staple and certainly one of the most popular foods in Asia, where similar types of noodles can now be found everywhere from Singapore to Seoul.

Last year, the Japanese consumed close to four-and-a-half billion servings of instant noodles. Who eats ’em, you ask? The answer is everybody. Literally. A survey carried out by the Japan Instant Food Industries Association revealed that only seven-tenths of “me percent of all young Japanese have never experienced a ramen snack, and even among adults this figure remained below three percent. This translates into slightly less than 40 servings a year for every man, woman and child in Nippon. Lined up end to end, all the packages of ramen consumed each year in Japan would encircle the globe no less than 13 times.

Anniversary

Next year, the venerable institution of instant ramen is due to observe its 30th anniversary. Its great ancestor, the Yellow Emperor of instant noodles, was introduced by Nissin Foods company of Osaka in 1958. (Exports began in 1960.)

Following on the heels of Nissin’s revolutionary product, other companies soon started cranking out their own ramen varieties. Sapporo Ichiban, a popular brand put out by Sanyo Foods, featured a choice between salt and shoyu flavors; early versions of Myojo ramen meanwhile contained, in addition to soup, a packet of dried menma — four or five fat sticks of preserved bamboo shoots — to break the bleak monotony of the noodles.

Incidentally, the word ramen itself is sometimes written with the Chinese characters “la-mien,” but these are apparently used for the sound without any particular meaning in Chinese. By far the most common way to eat them is in soup; each summer, nevertheless, a Chinese-style dish garnished with sliced ham, cucumber, fried egg, grated ginger and kamaboko called hiyashi chuka makes its appearance for the duration.

Faster Food

In 1971, the second ramen boom was launched with the advent of “snack” noodles, i.e., those dispensed in the now-familiar styrofoam cup. One immediate advantage to this development was that it enabled sales of instant noodles from vending machines. Incidentally, while surveys indicate that roughly two-thirds of adult ramen consumers prefer the packet type over cups, Japan’s young people are split almost precisely down the middle on this issue.

Manufacturing instant ramen is a rather involved process. Once “pulled,” cut and separated into individual portions, the raw noodles are fried in hot oil for about 120 seconds, reducing their moisture content from as high as 40 percent to around two percent. They are then rapidly chilled, subjected to weight and other quality control inspections and finally packaged with soup stock and other ingredients.

In 1969, a new “Alpha” process was developed which made it possible to dehydrate the raw noodles at high temperature without oil. Although production time is longer, the Alpha process allows users to prepare them more quickly, and the taste is said to be superior to the boiled-in-oil variety.

Because preservatives are not used, the shelf life of instant ramen is not long; manufacturers generally advise consumers to polish them off within four to six months.

A Measure of Success

Like everything else in this country, ramen is also invited to run the gamut of statistics; and man, do those Japanese love statistics. For example, they will tell you that there are an average of 79 noodles in a single package, the individual length of which is approximately 65 centimeters. Lined up end to end, therefore, a package of noodles will reach an astounding 51 meters. This means that if you eat your quota of 3.3 packages a month you may assume that you have strung out on pasta for a total of 168 meters — about the length of two football fields.

Other trivia:

• Some 318,000 tons of wheat flour go into the making of instant ramen each year, or about 7.5 percent of all wheat consumed by Japan.

• There are currently some 452 established ramen products on the market, of which envelope package types number 286 and snack noodles 166. A spokesman at Myojo Foods Co. remarked that each year manufacturers introduce around 100 new types of instant noodle products in Japan. Of these, only a few manage to survive more than a year. The Japanese, apparently, are nostalgic when it comes to noodles.

• Unlike some Japanese foods, such as shoyu, which are sometimes modified to appeal to regional taste preferences, any specific brand of ramen is the same throughout the country. (Manufacturers are, however, very much aware that some varieties sell better in a given locale.)

• Instant ramen has proved its mettle at holding the line on inflation and remains a “best buy” product. As opposed to 440 and 730 percent increases for rice and tofu respectively, retail prices of ramen have gone up just 2.3 times since 1958.

• A package of ramen runs from 350 to 450 calories — corresponding to 12 to 14 percent of the recommended daily requirement for an adult Japanese.

• Japanese exports of ramen last year went to 58 countries and reached 7.32 million kilograms in volume, with a value of ¥3.5 billion. Since production long ago began to shift from Japan to overseas, this figure has not really grown since 1969, a record year in which 12 million kilos were shipped.

Although information on caloric and nutritional values may be in dispute, I am pleased to inform that instant ramen is surprisingly free of undesirable ingredients; although many tend to believe otherwise, ramen contains no preservatives, food coloring, binders, emulsifiers, etc. On the other hand, no one is suggesting that you attempt to survive exclusively on a diet of cup noodles as this may result in scurvy — not to mention a chronic case of indigestion.

It should also be pointed out that real ramen, the kind served in restaurants, has been around for years. It is made with “nama” (fresh) noodles, and suffice to say any detailed study of their particulars must be left to someone with a stronger constitution than yours truly. I would nonetheless offer that, in addition to the orthodox Chinese variety, restaurant ramen is frequently classified by regional types (Hokkaido and Hakata being two popular examples), and some aspects of these cooking styles have, of course, found their way into the instant variety, with limited degrees of success.

Rattle Those Pots & Pans

Now, let’s get down to the real nitty-gritty on how to eat the damn stuff. Certainly all of us by now know that the ramen packaged in paper is generally boiled in a saucepan for several minutes and any other ingredients poured in upon completion. To prepare snack noodles, the lid is peeled back from the edge of the styrofoam cup, contents removed from their envelopes and sprinkled over the top of the noodles.

Then boiling water is added and noodles are covered and allowed to steep for several minutes. It is recommended that instructions provided on the package regarding boiling time, quantity of water, etc., be followed to the letter, er, kanji.

But are there any secrets to whipping up an exceptionally tasty bowl of instant ramen? This reporter consulted with Madam Lee, a local Chinese food expert who also happens to be his better half. Discounting the idea that deluxe ramen offers anything resembling gourmet food, the Madam sniffed and remarked, “Gou pee!” (a Chinese expletive politely translated as “nonsense.”) “Anybody who can boil water will tell you just to buy your own plain noodles and put in whatever you like.”

You can disregard those luscious illustrations on the outer package; they are totally misleading and most carry disclaimer in Japanese such as “meshiagari-kata sanko-shashin” or “chori retsu” (suggested ways of preparing). In actual practice however, the more loving preparation that goes into the making of ramen, the better the result.

Anyone will tell you that the secret of good ramen is “gu” (pronounced “goo”). Gu are what you put in, and that could range from last night’s leftovers to canned Spanish anchovies. One survey here revealed that the three most popular gu for men, women and children are naganegi (Japanese leek), Chinese cabbage and raw egg respectively. Other popular items include bean sprouts, pork, ham, spinach, wakame (a variety of seaweed), carrots and hard-boiled eggs.

Japanese food is currently in the throes of an “ethnic” binge, and certainly the most noticeable trend over the past year or so has been the popularity of highly spiced varieties. Some of the more visible contain red pepper powder, dehydrated Korean kimchee and/or other tongue-zapping formulas.

The Ramen Review

Confirming my worst suspicions, a concentrated and persistent assault of instant noodles on the lining of one’s stomach will prove a sure path to dyspepsia. Halfway through a solid month of noodle lunches, I swear I could sense impending indigestion just from looking at the designs on the packages. Tastewise, though, some varieties proved a pleasant surprise. (As discounting is widespread, prices have been omitted)

Packet noodles

House Tantanmen—Separate packet of sauce contains fairly potent mixture of sesame, peanuts, red pepper. Don’t eat before bedtime unless you have Alka-Seltzer handy.

Maruchan “Tempura soba”—Buckwheat noodles and therefore easier on the tummy. Don’t expect to stumble upon a plump, juicy prawn; the tempura is in the form of age-dama.

Myojo “Charumera” miso ramen (w/sesame) —Probably a good mixer with other additives but rather bland by itself.

Myojo Chukazanmai—A high-class product known to be popular for its versatility.

Nissin Chicken ramen (miso flavor)—Somewhat unusual in that these noodles can be prepared by placing in a bowl and pouring boiling water over them. Indented area in center leaves space for a raw egg.

Sapporo Ichiban Hotate-aji Ramen—Noodles are so-so, but package includes highly tasty broth made from scallop base. A good choice if you work at it.

Snack noodles

Escokku Hashire! Gyuchan niku udon—Udon with some meat included. Taste was slightly above average, but preparation a bit inconvenient as meat contents must be heated atop bowl.

Escokku Yakibuta Ramen—Chinese style with sliced pork. Satisfactory.

Escokku Wakame (w/sesame & miso)—Easy on the digestion and reasonably tasty.

Kanebo Tempura soba—Not even close to what one could expect in a restaurant, but acceptable as an instant food.

Maru-chan Hanten yakibuta ramen—another roast pork variety; aji wa ma-ma dake.

Myojo Men’s Club Otoko no Sutamina “ninni-ku” tonkatsu ramen—Fails to live up to its macho image. Barely enough garlic to wrinkle a sensitive nose.

Myojo Men’s Club San-mai Chashumen—The three slices of roast pork were a bit on the skimpy side; otherwise OK.

Nissin Seafood cup noodle—Absolutely tops. The great chefs of Europe might not agree, but this has got to be one of Japan’s tastiest, most economical snacks.

Toyo Suisan Mabo ramen—Supplied with spicy Chinese bean curd condiments. Better than average.

Others

Karaijan “Hot Shock” yakisoba—Only mildly spicy; principal taste is the strong sweet sauce typically served with yakisoba. Red pepper unable to deliver as promised.

House Range Gurume sauce yakisoba—One of the new breed of popular microwave-ready dishes. Just add sauce and put in oven. Convenient, but not especially good.

Maruchan “Kare-udon”—Curry-flavored noodles. Ugh. I never could understand why the Japanese like this OD-colored slop. Wear an old shirt when you eat it.

Nissin “Zaru soba”—Not bad, if you like cold buckwheat spaghetti with green horseradish and seaweed.

Nissin dry curry (instant rice)—Clever container design allows user to steam rice by adding boiling water, draining and then setting container upside down. Much better instant rice dishes are available in the frozen food section.